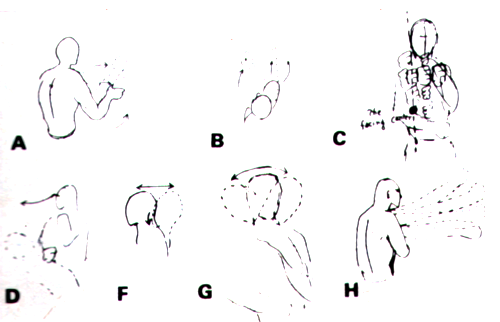

The efficient use of the leading hand is a science all of its own. In the section of Bruce’s book describing the leading straight punch, there are a group of illustrations titled “The Elusive Lead.”

Very little explanation accompanies these drawings, but they could be categorized into two basic thoughts – the elusive path of the punching hand itself and the elusive body motion that may accompany any leading punch.

Drawings A and B describe the straight or curved paths the hand may follow by illustrating the motions of a straight punch, a hook and a backfist. There are of course others like the rising uppercut or the hanging punch that curves downward and so on.

Even the straight punch may vary its path to score on the moving target or hit in the momentary opening. Drawing C suggests this elusive straight lead and other elements that we’ll cover another time.

The next three illustrations describe some of the upper body motions possible. Figure D is especially interesting, since it may be interpreted several ways.

Mainly, it suggests a short, straight forward motion of the upper body during the initiation of the punch. As the punch continues, the body may then angle to one side or the other to avoid an incoming counter punch.

Such a movement may also serve as a feinting motion to open a target on the opponent or to gain some movement time by enticing him into launching a counter movement in the wrong direction. The figure could also represent a simple evasive motion to secure a better position from which to punch, elbow or begin grappling.

Figure F simply describes the motion of a snapback. Executed on the border of the opponent’s full reach, it will take the fighter just beyond the extension of a punch without moving the feet and will allow him to follow the retracting fist in to deliver a riposte (counterattack on the same line) or a counterattack on a new line. The snapback is a handy device that needs a slightly forward center of gravity to execute really well.

Figure G illustrates a side-to-side movement of the head. This may accompany or precede the slipping motion described by figure D. It may be aided by a parry or it may in extreme situations be used alone. Any movement that takes the neck out of its straight, supported alignment behind the lead shoulder, however, is usually considered an extreme defensive action used only in emergencies.

With the exception of figure H, which probably illustrates the same things as figure C, the rest of the drawings deal with angling the body and fist simultaneously into one of the “four quarters.”

The four quarters are described in fencing books and in the Wing Chun style of kung fu, but neither accentuate the body motion quite as much as Bruce did. The body motion is more an adaptation of boxing.

The hand and body motion used simultaneously into the same quarter is a good variation from the previous hand and body motions described that often separate into different quarters, such as slipping low and hooking high.

The combinations are endless and the most important things to remember here are variety and awareness of the opponent’s movement.